A Closer Look at the Goodwin House: The North Wing of the Mary Washington House

Michael G. Spencer

While the south wing of the Mary Washington House, the portion in which Mary lived, has received quite a bit of attention over the years, the Goodwin or north wing of the building has remained shrouded in mystery. However, as students in HISP 461 have looked into the history and begun to examine the materials of the building it has become increasingly apparent that the building is a contemporary of the south wing or Mary’s House and likely dates to the 1760s. Both the south wing and the Goodwin House were likely constructed by Michael Robinson between 1761 and 1771. The first concrete mention of a building, of which I am aware (aside from standard deed/legal language which can often be misleading) is a reference made in one of George Washington’s letters noting that his mother Mary has picked a “commodious house, garden and lotts” in Fredericksburg in which to reside (“From George Washington to Benjamin Harrison, Sr., 21 March 1781,” Founders Online, National Archives). However, as was typical at the time, a number of ancillary structures or dependencies were likely also on the property. This could include everything from a smoke house, dairy, outhouse and separate kitchen. Today, no known original 1760s dependencies exist (the log kitchen likely being late-18th or early-19th century, more on the reasoning shortly) with one possible exception, the Goodwin House. There are a number of reasons why this theory may hold some truth.

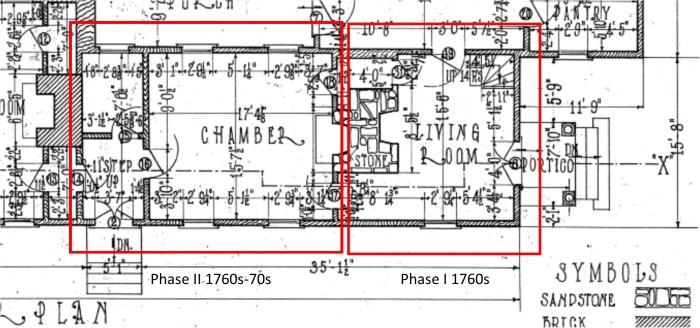

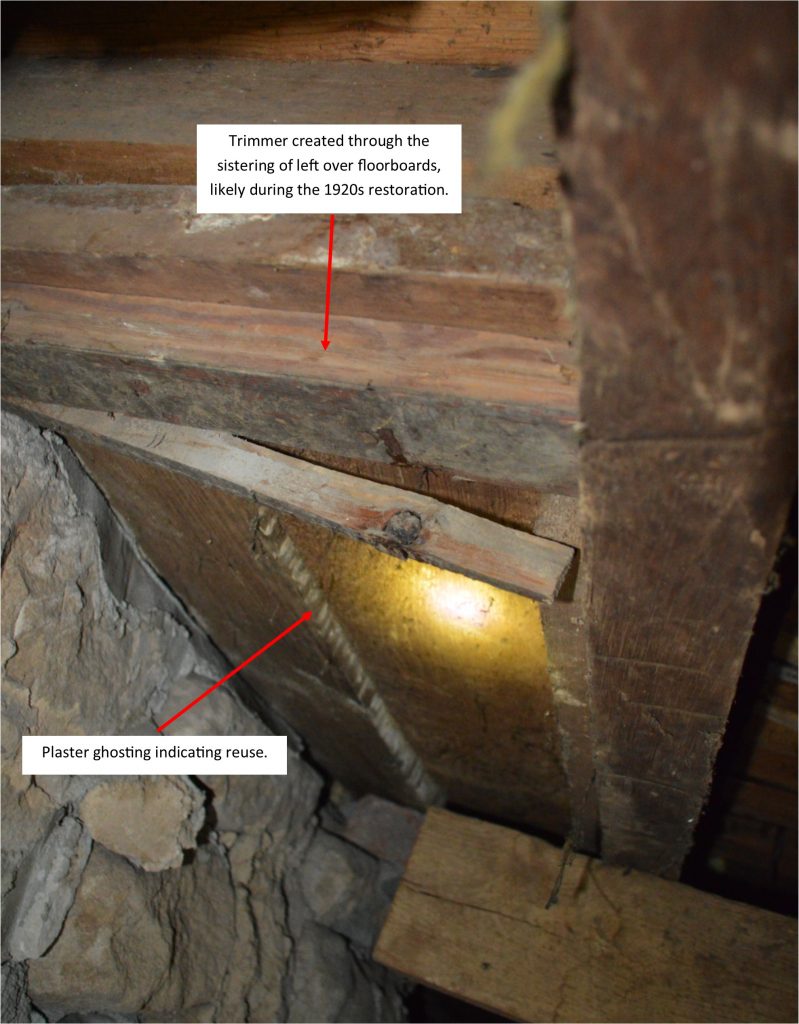

First, the date of construction of the first and second phases of the Goodwin House seem to coincide with that of the south wing or Mary’s dwelling. Both buildings exhibit hand hewing and pit sawing techniques as a means to fabricate their wooden structural members, both techniques were typical of the 18th century. Additionally, both structures possess sandstone foundations, a material found in many 18th century Fredericksburg buildings. Wrought nails, again dating to the 18th and early-19th centuries are also found throughout both buildings. These aspects are all things the two, once detached buildings share in common. However, the use of puncheon floor joists, joists left “in the round”, in the north section of the Goodwin House wing seems to indicate faster, less expensive construction, than the pit-sawn floor joists found on the south wing or dwelling house.

The Goodwin house also possesses a massive sandstone chimney stack, which while much altered, seems to denote a cooking or food preparation function as opposed to just heating the building. While the base of the hearth on the north side of the chimney stack was covered in concrete during the 1920s/30s alterations, the placement of some stones seems to indicate a much larger firebox and hearth than what currently exists. On the south side of the chimney stack there is also evidence of a larger hearth and firebox at one point. The use of the Goodwin House as a kitchen during the time of the Robinson’s (1760s) and later Mary’s occupation would seem to fit the archival record as it is not until 1805 that we get the first mention of the current, extant log kitchen.

The linear arrangement and relationship of the south wing with the Goodwin House is also typical of other Fredericksburg lots during the 18th century that possess a series of dependencies. One has to only go a block north to the St. James House (ca. 1760s) to see a similar layout. Here the original wood frame kitchen is noted in Mutual Assurance policies as being directly to the north of the dwelling house fronting Charles Street. Other St. James dependencies follow suit including Mercer’s law office which is noted as being to the south of the dwelling house along Charles Street and in the right-of-way of Fauquier Street. In the case of the Goodwin House, the original portion of the building is located roughly 20 feet directly to the north of the south wing or Mary’s original dwelling house.

Such evidence is currently indicating that while distinct from Mary’s dwelling house the Goodwin House was likely integral to domestic operations during Mary’s tenure.

Leave a Reply